Thomas Lojek

Interview with

Ralf Kassner:

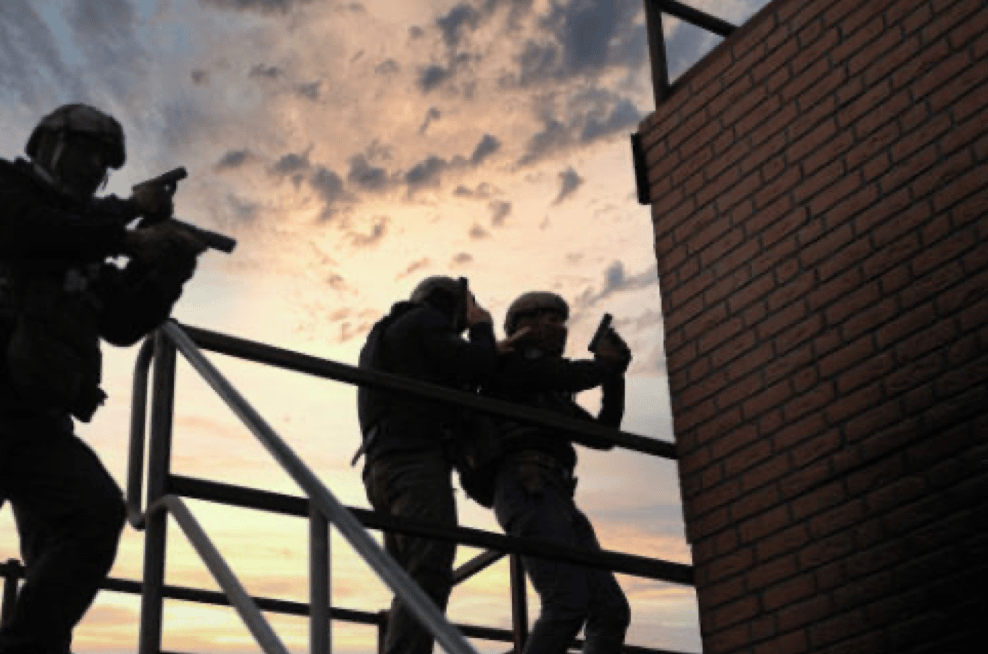

Kill House Training For Close Protection Services

Ralf Kassner is a former member of Germany’s elite counterterrorism unit GSG9 and SEK.

He is founder and CEO of Wodan International, a German Risk Management company for comprehensive security solutions offering services in the areas of consulting, management, risk assessment and security services.

Thomas Lojek: Ralf, as a former SOF unit member (GSG9 and SEK) and CEO of Wodan International, you are a leading European expert in kill house training and 360-degree tactical training.

What tactics and scenarios do you have in mind when you set up a kill house training session for close protection professionals during a Wodan Security training event?

Ralf Kassner: First of all, kill house training is not so much about cutting-edge shooting skills and heavy live fire action, as someone might think. A good kill house training, especially for close protection services, is very much about coordination, communication, speed and building up operational pressure.

The training should make you able to build teams and then operate effectively within these teams, even with people you may just have met for the first time. Because this will be a situation that you will face very often during your field operations as a close protection service professional.

It happens all the time. A company puts you in a new team, maybe one of your team members got hurt, another one leaves the company, or the overall operational parameters are just changing — whatever it is: the most reliable constant in the close protection service business is change. The grade of your professionalism in this business is your ability to make yourself comfortable working with strangers under tremendous pressure and in challenging or even lethal environments.

We do not talk about SWAT or military SOF training here, where unit members have time and significant resources to study their team members’ operational behavior — often for months and sometimes for years. Close protection services, especially in the private market, is a different category of specialized operations and has to deal with limited resources, restrictions and a lot of unknowns.

Therefore, a 360-degree training for close protection should be about flexibility — operational and individual flexibility. Teams, operational parameters and objectives can change very quickly. Your training should reflect that.

Fast and effective coordination of close protection service professionals

Thomas Lojek: Let’s take a common scenario.

There is a business meeting of Fortune 500 CEOs, and the worst case is happening: an active shooter is in the building.

How do you prepare your trainees for this kind of incident?

Ralf Kassner: Interestingly, in most cases the biggest challenge, especially in the first crucial minutes or even seconds of the incident, won’t be to deal with the threat, but to have fast and effective coordination of all close protection service professionals at the scene. Somebody has to take the lead — building a team!

Your scenario implies an incident at a larger business conference.

That means there will be various close protection professionals at the site, all with different backgrounds, skill levels, and experience.

They will differ in their training and in their equipment.

Some have a military background, others come from law enforcement, and a few, maybe, have no professional background at all.

You will have a lot of people around who counter this situation with different tactics and different field experience — but they all will be in a rush to protect their own VIP.

This can be quite a challenge.

Different levels of fitness, reaction time and speed in close protection

Thomas Lojek: Could you give us a concrete example why this could be such a challenge?

Ralf Kassner: Sure. Let’s talk about something that might seem insignificant at first but can have a huge impact on the outcome of the situation: what if you have to run up several storeys or through a long corridor before you get to your VIP?

During some conferences the close-protection teams are ordered to wait in a different part of the building.

It is very unprofessional conduct by event management, but it still happens on some occasions.

Even your VIP sometimes asks you to wait somewhere else while he meets his business contacts.

So somehow you are not close to your VIP when the shooting starts.

Now we have a bunch of hired guns in high-modus.

And even assuming that we are talking about well-trained individuals here, we still will have different levels of fitness, reaction time and speed in this group.

An uncoordinated armed group under stress, with significant gaps in experience, fitness, reaction time and stress resistance, can turn a few seconds of running down a long corridor into an endless nightmare.

Because now you do not just have to worry about the active shooter somewhere in the building, but also about several armed individuals under stress around you — individuals you don’t really know, who may have a much more nervous trigger finger and a lower tactical skill level than you do.

Keep in mind that there is no way to capture all sides of the discussion in a limited article, and it would invite further discussion.

Small differences in individual experience can add up to big problems

Thomas Lojek: So, frankly speaking: in close protection services the individual backgrounds and differences in training and fitness levels within a random group of professionals at the site of an ongoing situation are nothing less than an additional risk factor.

Ralf Kassner: Yes. Small differences in individual experience and training of operators at a situation can add up to big problems in close protection, especially if you haven’t met these operators before.

If you don’t know them, and if you don’t really understand their background, it can be hard to gauge.

The new guy next to you could be just an ex-bouncer with a gun.

Another one might be a highly skilled Army SOF operator.

But his background in military operations doesn’t mean that he is also a great close protection professional.

In this situation we are just a bunch of individuals with guns and different skills and backgrounds who have to solve a big problem very quickly.

Most likely, we have to solve this problem in a lethal and distressing environment full of panicking people, fleeing crowds, maybe in smoke or fire, with bodies around or very badly hurt people — while blood and screaming seem to come from everywhere.

In this environment, a group of hired guns without coordination only adds risk to the situation: the risk to get shot by one operator who acts unprofessionally or too nervously; the risk to miss the threat, because keeping an uncoordinated group in check means too much distraction for you; or the risk to harm innocent bystanders.

There is also the risk of getting into trouble with arriving police units who don’t know who you are beyond the fact that you are carrying a gun in a building with an active shooter.

If you cannot handle this type of situation effectively and at least with a basic structure of essential teamwork, the presence of a randomly assembled group of close protection members will only make things more complicated.

Therefore, a good kill house training or any form of 360-degree live-fire training should not only be about precise shots at bad guys, but also about challenging your team-working skills and your ability to reach a professional level of flexibility in any form of tactical coordination.

You have to read and understand people.

You have to anticipate their reactions and their ability to deal with a threat, or with innocent bystanders, distraction and tremendous stress.

It is people skills.

If you get good at it, you will be able to team up with different individuals at any incident and, in the best case, establish a life-saving 360-degree team securing your operational progress in a mission even with strangers.

But you have to train for it.

Building operational pressure and speed

Thomas Lojek: Now, let me challenge a few points of view: in the context of training for close protection, does it mean that shooting is less important than the training of your soft skills like teamwork, communication and building rapport?

Ralf Kassner: We train for highly complex and very challenging situations.

You can‘t break down these complex challenges of a real operational combat situation into such a simple formula, like soft skills are more important than shooting skills or vice versa — because it is not true.

You have to put a lot of different pieces together when we talk about training for a situation that may decide if you and other people will live or die.

Coordination and communication are key elements.

Decision-making under pressure is highly important.

Your ability to see and to really understand your surroundings under tremendous stress is crucial.

Building operational pressure and speed is essential. Shooting and your shooting skills are very, very important. Accurate and good shooting skills are the heart of our profession.

But you should also always keep this in mind: your gun points exactly in the direction it does and does only what your current perception and your imminent interpretation of the given situation tells you to do.

If you shoot quickly and accurately, that’s fine — it’s a great skill and it is important.

But this skill will make the worst day of your life if you shoot too fast and too accurately during an incident just because someone moves quickly in front of you and seems to carry a weapon, and later it turns out that it was one of your close-protection buddies who was trying to reach his VIP over a different route within the building.

See?

It’s more than just shooting, and it is more than just soft skills, communication skills, and teamwork.

In a highly stressful situation like an active shooter scenario with crowded floors, panic, screaming, maybe smoke and fire, it can easily happen that you shoot the wrong person when there were no steps of coordination and clear communication between the close protection service operators at the site before the shooting started.

If you only learn to shoot at everything that has a gun during your live-fire training, you won’t be prepared for scenarios where other close protection professionals are with you in the building, or even worse, when you run into arriving police forces.

You have to go through these kinds of scenarios in trainings to avoid fatal decisions later in real-life incidents.

So, it will be a solid mixture of very good shooting skills, soft skills and a lot of experience that will make a highly professional close protection service member. It wouldn’t make sense to weigh one skill too much over another.

You have to aim for the full package — or you become a one-dimensional “expert” in a multi-dimensional threat environment, which means nothing other than: “You get killed!”

Within seconds you have to coordinate yourself with people you barely know

Thomas Lojek: How do you train this with the attendees of your courses?

Ralf Kassner: In our Wodan Security trainings, when we work with realistic live-fire scenarios, we always try to bring professionals together who have never trained before as a team.

We try to mix up all teams constantly.

This is important.

If you have an incident in a complex environment like an active shooter scenario, you have to demonstrate good skills in efficient coordination and communication.

A real attack happens so quickly.

Within seconds you have to coordinate yourself with people you barely know — who will take the lead, who will cover the back.

You have to communicate your evacuation routes with strangers quickly, clearly and effectively, and you may have to deal with arriving law enforcement units.

And let’s be honest: a real-life incident may force you to work with somebody who really, really sucks.

You better be prepared for that.

So, first: in our trainings there will be no fixed teams, but a lot of randomly mixed-up groups, to make our attendees have useful lessons in how to handle any kind of tough operational coordination situation and to gain operational flexibility under pressure.

Second: in our trainings we confront our attendees with scenarios that teach them something about operational pressure and speed.

Like in your active shooter scenario, we bring them into situations where they have to make very fast, very difficult decisions with serious consequences.

Within seconds everybody has to act and know what to do: can we establish teams for 360-degree securing?

Who will be in charge of an evacuation?

Is there any order in getting the VIPs out?

Will we gather them together in a safe room first?

Or will we try to get them out of the building as fast as possible?

If you take all that into account, your serious kill house won’t be solely about the thrill of a live-fire run anymore.

It will become a complex challenge. And that is what we want for your training.

And third: it all has to happen in a close-quarters environment.

You must be able to handle shootings at very close distances — this is not a shooting range.

During a real incident, you will have to run around objects like tables, chairs and decorations, maybe through smoke, fire, low light and panicking crowds.

Our training simulates these challenges by getting our trainees into a close-quarters environment where they have to handle all kinds of operational pressure.

So, essentially we set up training runs that test your coordination, your operational efficiency and your ability to fight in a close-quarters environment.

Make sure that all know what to do if an incident occurs

Thomas Lojek: Could you give our readers some tips on how to do this in real life?

Ralf Kassner: For example, if you are with your VIP at a bigger conference or a board meeting, normally all close-protection professionals are gathering together in another room nearby and they wait.

Instead of just killing time, it will always be a good idea to talk with your colleagues in the room.

An investigation of the building, evacuation routes, alternative routes, risk spots, gathering spots or safe rooms — that should be a no-brainer.

Establish at least a quick scenario routine to make sure that all know what to do if an incident occurs.

Be careful: don’t lecture anyone or come across with an annoying “I am the team leader, here” attitude.

Be respectful, and consider that you are talking to people with a certain degree of professional experience.

But make sure that there is a certain concept of: if we have an incident…

Who will take the lead?

Who will cover the back?

Can we build teams?

Can we leave this room as 2-man teams or 4-man teams for a 360-degree cover?

Do we know our extraction routes?

Do we know all alternatives to the main extraction route?

Will we be able to identify each other quickly?

What to do if we get separated?

What kind of equipment do we have?

Anti-ballistic shields?

Vests?

TCCC equipment?

Where is the equipment?

When you have to arrange all this while an active shooting is going on, you will be in a very tough spot.

Let’s keep in mind: the average active shooter incident lasts about 12.5 minutes.

Within 12.5 minutes you have to handle a complete team setup and a bundle of very complex operational decision-making.

With these kinds of odds, I would rather not bet my own life, nor my professional career, nor the lives of other people.

You should be prepared before you get into this tough and very narrow time frame of a real-life shooting.

That’s why you are a professional.

A professional attitude towards close protection services means for you to talk, to communicate and to make sure that there will be a plan or at least a basic coordination between all close protection service members in the building.

This is not the “John Wick Way of Life,” but it is the right thing to do for every close-protection service professional who is serious about his business and the people he has agreed to protect.