Thomas Lojek

Interview with Kris Paronto:

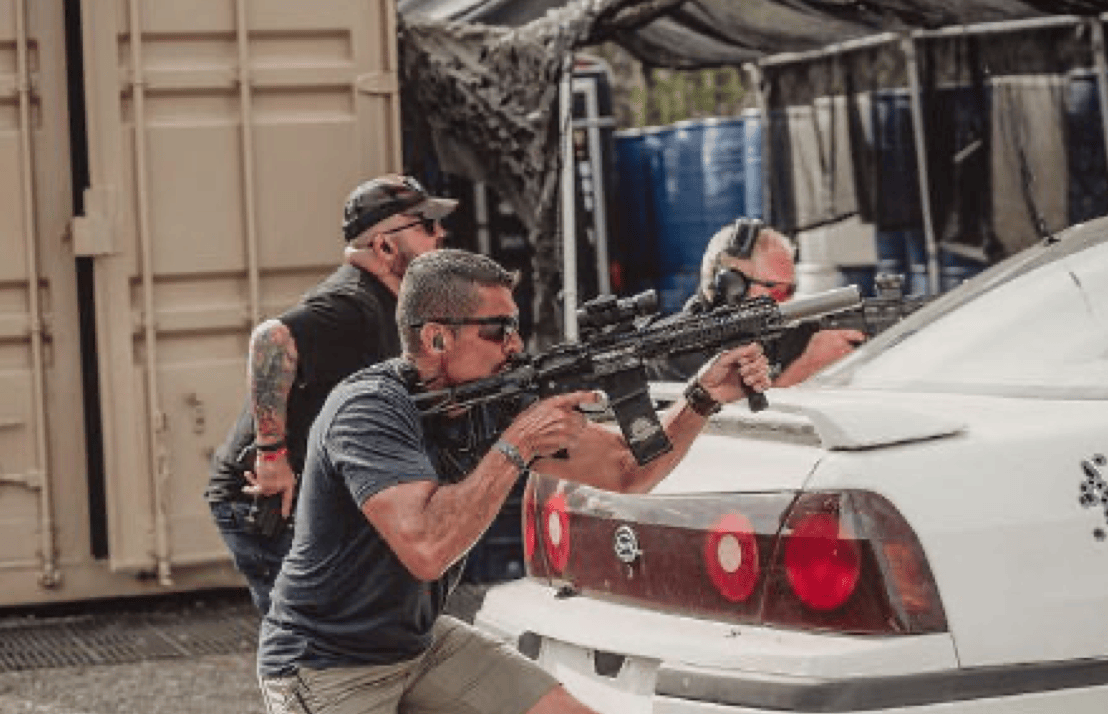

Effective Tactical Decision-Making in Dynamic Situations

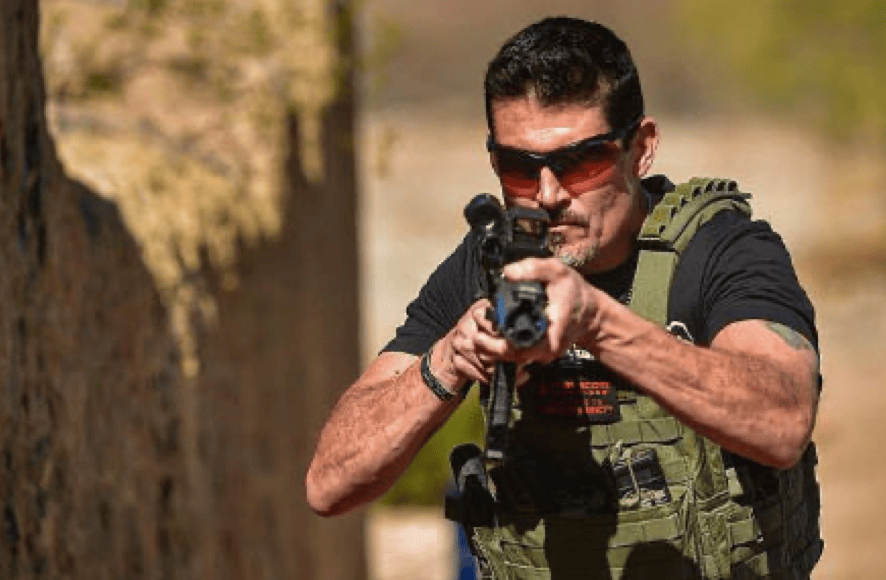

Kris Paronto is a former Army Ranger from the 2nd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, and a private security contractor.

He was part of the CIA annex security team that responded to the terrorist attack on the U.S. Special Mission in Benghazi, Libya, on September 11, 2012, helping to save over 20 lives while fighting offterrorists from the CIA annex for more than 13 hours.

Kris and his fellow brothers-in-arms’ story is told in the book 13 Hours by Mitchell Zuckoff. In 2016, their story was adapted into the film 13 Hours, directed by Michael Bay.

Today, Kris Paronto is a New York Times bestselling author, a highly sought-after public speaker, and he continues to train carefully selected groups of operators through his company, Battleline Tactical.

Official Sponsors

Gaining a lot of experience in and out of combat zones

Thomas Lojek: Kris, you are still very active in the training sector.

Could you explain what you are doing and what your focus regarding your training business is?

Kris Paronto: I served with 2nd Battalion 75th Ranger Regiment, and later as a private security contractor for various private security companies to include Blackwater Security, SOC, and direct hire for the CIA long before the Benghazi attack happened.

I spent a lot of time in beautiful countries like Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Libya, etc….

And they are beautiful countries, really. It’s savage beauty, but beauty nonetheless.

I worked overseas for over 10 years, gaining a lot of experience in and out of combat zones.

In between deployments I would come back to the US and work for Blackwater’s High Threat Protection OGA program as a Lead Instructor.

This allowed me to apply the tactics we were teaching in the US to real operations.

I was able to see that tactics that may work in a controlled environment may not work in an uncontrolled environment.

I learned so many valuable lessons during these years… learning from other operators and instructors, and then being able to practice my craft as an instructor in between deployments and at times during deployments as some required us to teach and train Afghanis on firearms, force protection and tactics.

I started Battleline Tactical in 201 7, approximately four years after I left the CIA’s GRS Program.

I had not been actively deploying or active in the training sector and felt the draw to get back into training others.

Battleline Tactical was started in the hopes of passing on knowledge that had been passed down to me, but also for me to get back into the firearms community.

We originally started a few years ago.

It was myself and a former GRS Teammate, Dave Benton.

Since then, Dave has since departed, but the team gained Former 1 st Batt Army Ranger Ben Morgan, Former MMA Fighter and multiple black belt holder Benny Glossop and Former Army MP Jeremy Mitchell as lead and assistant instructors.

We also partner regularly, teaching joint firearms courses with outstanding fellow instructors Daniel Lombard of Davad Defense, the Mauer Brothers of Treadproof Training, Paul Braun of Maxim Defense Academy and Brad Dillion and his crew of excellent instructors at Red River Gun Range.

We do have an excellent team, and as of right now, we primarily conduct mobile training.

In the past, we have looked for ranges and facilities around the country to conduct our courses, but we now primarily use Davad Defense’s facilities in Crete Illinois and Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, Defender Outdoors in Ft. Worth, Texas, Treadproof Training in Nunnelly, Tennessee and Red River Range in Shreveport, Louisiana.

Everything and everyone are constantly moving

Thomas Lojek: Tell me about the training?

Kris Paronto: We do a wide range of training, from stress fire training to basic pistol or basic rifle, which is great.

All of them are satisfying, but I have to say my favorites are still the novice classes.

It’s especially rewarding to see the confidence grow in a new shooter.

During my blackwater days as an instructor and student, we traveled to many training sites around the country, and I always felt that there was a lot of standing around talking.

There was too much talking by instructors about themselves, long drawn-out Powerpoint presentations, and most times, instructors talking, not so much about the lessons they learned from their experiences, but trying to validate their credibility.

However, the instructors that I learned the most from got us in, briefed us on course expectations and course curriculum, then got us out on the range.

They demonstrated tasks and had us work on the tasks right there on the range making spot corrections when necessary.

So, at Battleline we wanted to expound on this latter.

Yes, we need to talk to instruct, and sometimes that means you have to stand up on your soapbox and tell the participants what we have done or explain why we conduct a tactic in a certain way to provide the example as to why that tactic did or did not work in real time.

But I felt that it always went from instruction to “Hey, look what I have done… Look how cool I am… I got all these experiences…”

As a student or fellow instructor, I didn’t want to hear that.

That was the part where I started to tune an instructor out and learning suffered.

When the motivation to be mentally present in training drops, the quality of the training always suffers, and in the end, we have become ineffective instructors and failed the student.

So we, at Battleline Tactical begin to apply training another way.

I used my experience playing varsity sports throughout high school – football, basketball, baseball and track which led to playing NCAA Football – as a training model.

I thought to myself that firearms training and tactics is nothing more than a sport, and an instructor is nothing more than a coach.

Coaches are there to teach, lead, motivate, mentor, and bring the best out of an individual.

Football practices are also constantly moving, going from training station to training station with little, unnecessary talking by a coach, unless it’s to make a spot correction or demonstrate the task to be completed.

There was little standing around.

And I took this experience and made it the fundamental principle of the training courses at Battleline Tactical.

We generally have fairly big classes, but they can fluctuate.

Thirty people or more in a firearms class is a big number of participants for a training class.

So, we split them into separate groups of 10 people, conducting the training that is associated with that course.

For example, for our gunfighter course, we’d divide a group of 30 up, putting 10 people into combatives, 10 others at the pistol range and 10 at the carbine range.

And we rotate every two hours.

You have two hours, now focus on the task, self-correct when you make mistakes, and don’t forget to smile and have fun.

We don’t rest too much between the rotations because, as a Ranger or football player, we didn’t take many breaks until the training day was complete, so it’s just my style.

It makes our classes highly dynamic, focused, but most of all enjoyable for everyone, from the novice to the experienced.

Everything and everyone are constantly moving.

Instruct, demo, train not over talking.

This is the death of many courses: too much talk.

Thomas Lojek: How is the reaction of your students to your more dynamic training style?

Kris Paronto: It is fantastic. After the course people are tired, but they have a sense of accomplishment.

People love challenges, even when they don’t think they do.

We challenge them.

We push them enough to make them realize that they have accomplished something for themselves, and their confidence

grows.

There is not a lot of downtime, not a lot standing around, because I think this is the death of many courses: too much talk.

We lose the attention of the student.

Bring your students on the line, demo, train, assess, correct, re-demo if necessary, train, assess, correct, etc

Because it’s my belief we learn more by making mistakes, figuring out why we made those mistakes, fixing the mistakes, than by doing it correctly.

We learn more by doing, learning and doing again.

Let students learn valuable lessons by what they do in your course.

Don’t replace their hunger for having a unique experience with what you think would make a good story about yourself, unless that story can add to the training module at hand.

Challenge them to act, to move, to try out, to solve problems and to fail as well as to excel.

Of course, you have to make sure that everybody is safe, especially when you give your students room to make a few mistakes during a class.

Safety is a hugely important factor in Battleline Courses.

Make sure safety is 100% and then have the student’s carryout the training.

Let them make mistakes.

Let them learn through their own mistakes and let them learn with their own hands, with their own eyes, with their own heads while they are thinking and moving.

I guess you could call it dynamic learning.

It’s the most effective form of learning.

We aren’t instructors… we are coaches and mentors.

Thomas Lojek: How did you come up with this training style?

Does it have something to do with your career in the military and your years of contractor work?

Kris Paronto: It was straight pulled from football.

My dad was Division 1 football coach for the 1984 BYU National Championship team.

I grew up around football legends like LaVell Edwards, Mike Holmgren, Steve Young, Jim McMahon and Robbie Bosco.

I saw how Head Coach LaVell Edwards mentored and how his assistants like my Dad, Mike Holmgren and Norm Chow taught players that would later become greats in the NFL.

It was mentoring, not instructing, trying to bring out the best in the player.

The mentoring culture from an early age stuck with me, along with my own years as a player on the field.

Then one day after a course, I was doing my own self-assessment and I realized:

As firearms instructors, we aren’t instructors… we are coaches and mentors.

We are there to motivate and bring out the best of those who are coming to our courses.

Changing ourselves from being an instructor to being a coach, and becoming a mentor for those who look for our advice keeps the ego out of the training.

It is about our students and how they improve and not about our stories and our experiences, unless they reinforce a technique or tactic.

We create an experience for them, based on what we have done before, but not by what our status is in the firearms community.

There is a lot of arrogance in the world of firearms training.

Truth hurts, but it’s the truth.

And this arrogance is intimidating to new shooters, which stops those interested in firearms and tactics from getting into firearms classes.

Even in the professional sector and on a highly operational level this arrogance of a “tactical ego” creeps into training and causes damage.

It stops those on all experience levels from getting into or continually learning firearms and tactics and affects their true dedication to getting better every day.

At one point, the arrogance of having a rank or name replaces the most simple truth in a warrior’s life: There is always room for improvement.

So, we play it differently in our courses.

And what we do works wonderfully!

We get a lot of new people into our classes, who turn into enthusiasts, and that is humbling to us at Battleline.

We do also have a lot of seasoned pros, coming from law enforcement or highly experienced military veterans, who respect the training environment we create by our individual approach and also provide their own lessons learned and training point to the class, which we encourage.

For me, it is so great to see how it works: The beginners leave our courses with confidence.

And the pros with respect.

And that is what we want to see.

We want to see somebody smiling, because they feel that they have learned a little that they can improve with or provided a teaching point that will help someone down the line.

The best way to do it right is to learn multiple ways

Thomas Lojek: It sounds like your training style gives students more freedom to learn… to try, to fail, to figure things out for themselves.

But isn’t the nature of combat training, especially in the military, somewhat more dogmatic?

Where is the line for you between effective freedom in training and the pragmatism of dogmatic rules in training?

Aren’t there always a few things that have to be handled with:

“That is how it has to be done. Period.”

Kris Paronto: The thing with freedom vs. dogma in combat training is it’s always somehow like having our good old military kit bag with you: We want to throw so much in your kit-bag that we can pull it out when the situation arises.

And we want to learn many different things and ways to do it so we can handle any situation effectively.

But the only way to do this is to learn multiple ways and methods, so we can get into your kit bag and pull “a way” out to accomplish a task.

So, the essence of combat training is dogmatic per se, yes.

When carrying out an individual tactic or technique there normally is a most efficient way to do it.

For example, pressing the trigger with our index finger on our dominant hand is better than pressing the trigger with our pinky on our non-dominant hand, right?

What we are saying is that having different methods to employ the weapon is beneficial, but one way may be the best.

However, we still need to learn different carry positions, different ready positions, various retention positions, when to be dynamic with our movements vs methodical, because different situations will require different ways of completing the task.

The most effective operators are those who know this and who can employ different tactics habitually when various situations present themselves.

This cannot be done if we only learn one way or constantly train on one method.

Sometimes, the best way to clear the corner is to be methodical with your movements, enter with a high ready and pie the room methodically… but on other days, maybe the best way will be just to enter a situation dynamically at full extension, get in and dominate it, adding the element of surprise by your action.

But the only way to know the best way to do it right is to learn multiple ways and relearning them over and over…until they all become habitual.

And that is not dogmatic…

It is learning different ways to accomplish a task.

Fill your kit bag to the brim, then train and retrain everything you have in your kit bag until they all become habit-forming movements.

So, as an instructor, I am both.

Yes, sometimes one way is the best way to handle a situation or to complete a mission.

But the best tacticians know several different ways to complete missions and are able to choose the best way for that moment.

So again, it is like you opening your kitbag, you look in it and you have all this stuff there… and then you say:

“That is what I need right there!”

You grab it and start moving!

You don’t use a paring knife to cut steak.

You use a steak knife, but how would you know that if you’ve never held a paring knife or steak knife in your hand?

Here is one thing we really have to understand when we want to be more effective tacticians while under duress:

When I started in the military, it was all about being instinctive…

And I never liked the word.

I never liked the idea behind it.

If we are instinctive, it tells me that our brain is not working.

That’s incorrect.

Our brains are always working.

To me, it is “habits!”

It’s developing good habits.

Example – We continually put a car key into the ignition to turn it on (well we used to).

Over years of continually repeating this action we can do this with our eyes closed.

It is not instinctive, though.

We have learned it, because we have repeated those actions many, many times, so we know what to do without much thinking about it.

But it is a habit, not an instinct that leads us through that action.

It is the same thing with any marksmanship fundamental or firearms presentation.

The best option of using a high gun or low gun as we clear a building should become habitual, once we’ve completed the task 100s if not 1000s of times, because our brain is virtually moving you through the situation recognizing unknowns, building architecture and threats.

Our eyes are passing on to our brain what is around us, telling us “There is a window. I need to retract. There is a corner. I need to clear it. There are “friendlies.” I need to be aware of my muzzle and keep my finger off the trigger, indexing it above the trigger well and below the slide, etc. …

All this is not instinctive.

Our brain is telling our muscles what to do.

How efficiently we do it depends on how many times we’ve completed the task correctly.

So we train, doing it correctly over and over and over again.

Under duress, we all fall back to our highest level of training.

This is not because of instincts.

This is because our brain can only process split second movements we have continually trained as our senses become overwhelmed with our own thoughts and exterior sights, smells and sounds surrounding us in that moment.

We learn dogmatic pieces that are proven effective for us individually and as a team.

Learn as many pieces of dogmatic lessons for situations that demand flexibility and a choice.

Without the dogmatic learning process, you don’t have the freedom of choice to adapt to the dynamic situation later.

So, yeah… we have to look at both ways in good training:

We have to train dogmatically to get the basics down… but we also need to be flexible when applying them…

It sounds contrary, but it’s not.

It fits into the true nature of combat or any stress filled situation.

So, coming back to your question:

Yes, we have to be individually dogmatic, learning how to do something that is most efficient for “YOU” and then having it in your kit bag as an option.

Because the worst thing that can happen is us questioning ourselves when time is a factor.

The “What should I do? What should I do” countdown adds to the stress.

We cannot sit and wait our way for a situation where our lives may be in danger.

The worst thing to do is to make no decision.

But before that, we have to learn the basics, the fundamentals, and then continue to apply to those fundamentals in movements and continue to apply those movements to situations.

Then we train and retrain all situations, no matter how ludicrous it may seem at the time…

Then, when the happening that you hope never comes happens…

We’re ready for it.

We have learned all these different ways to actively respond, and now we have the options to act, whether it be methodical or dynamic, by inputting variables according to what is going on.

We cannot learn one single thing and use it in every single situation.

If we do we are setting ourselves up for failure.

But we can learn many single useful “ways,” applying them to the situations at hand and coming up with the best course of action, all in a split second if we’ve made them habits.

There will always be some variables that will change

Thomas Lojek: Flexibility vs. dogma in training.

How do you balance these two aspects?

How do you get people in your training to understand that they might need both one day?

Kris Paronto: Whatever training evolution you do, you should learn different methods to address different levels of training.

In combat training, we have to train for the moment when a threat or threats are in front of you, but there will always be some variables that will change that “one way“ we may know to handle the situation, so learning different methods to handle “one” situation will only benefit you.

Yes, there may be one way that is better than the others, but if a variable makes that “one” way impossible to complete then you better have a secondary, or even tertiary way.

What if you lose your hand?

What if you fall off a wall and you break your arm?

What if I have to break a finger?

How do I counter a threat then, when everything goes wrong?

And honestly, I learned the best when that monkey wrench was thrown into the mix, when that stripper named Karma came out of nowhere to destroy even the best laid method or plan.

As I told you, I learned a lot from my football coaches when I was young.

They gave me a certain set of rules and within the rules, they told me:

“Play and try what works and what doesn’t work, and learn from your mistakes and failures so when that situation arises again, you’ll know what to do.“

I have seen guys with a plethora of experience still make mistakes or lock up because they didn’t prepare themselves for that unseen variable.

Karma came in with a vengeance and caused havoc.

It’s happened to me as well, but first I was lucky to come out of the situation with all my fingers and toes.

Then I did my self-evaluation or required AAR while with the 2/75 and GRS and learned the hard way, in front of my peers, what I did wrong and what correction that would need to be made so I didn’t do wrong again.

One thing that I always tell people:

Even if you fail, you keep going.

Don‘t just stop and beat yourself up over the failure or mistake.

Learn from it in the moment.

It’s fresh and in your immediate memory.

Make the correction in your head, but continue to train and move forward.

That bullet is downrange and we can’t take it back, all we can do is readjust, re-aim and refire.

And this is where very dogmatic instructors can cause harm with their training style.

I’ve experienced it as a student and instructor:

Especially in room clearing or force on force scenarios:

The participant just stops when they make a mistake, almost freezes in place instead of continuing on with the drill.

When I’m the coach/instructor, they will sometimes look to me, like:

“Tell me something. What do I do?“

… and I’ll say:

“I don’t know. What do you think you should do?”

It’s not that I’m ridiculing or patronizing them.

I want them to continue to think because the worst thing in the world to do in a dynamic situation is not to make a bad decision.

It’s to make NO decision.

That was pounded into my head as a young Ranger private.

It’s that we continue to move forward.

We don’t stop or quit and we train through the mistakes …

… unless the mistake was so egregious that my squad leader deemed that we needed some on the spot correction, haha …

… and we keep finding work, keep moving forward.

I’ve been blessed to know, from experience, when shit goes sideways, we can’t quit.

We have to keep fighting, keep going.

I’ve made a lot of mistakes during my career, but I always kept fighting.

I kept moving.

That’s the Ranger-Mindset that I was blessed enough to experience and ingrain into my own personality.

We never stop.

The most well-laid plans go to shit all the time, but if we don‘t stop we’ll normally come out on top.

The I-quit-and-wait-for-advice-when-I’m-wrong habit is a dangerous mindset that grows around dogmatic instructors.

Instead, a more flexible training approach teaches people to keep going.

No matter what, you drive on, continue to complete the mission, then we go back and evaluate so we can dig into what was going through the participant’s head at the time the mistake was made.

I learned this quite extensively every Monday after a Saturday football game as we watched and dissected film of the game prior to going to practice.

Nothing will humble you more than sitting in a room of your teammates, watching a mistake you made over and over again in slow motion.

This also carried on to when I was with 2/75 after a mission or training operation, but it taught me how to be able to handle constructive criticism, as well as how to provide constructive criticism the correct way, without belittling the person it’s being directed to.

The Ranger instructors put us under tremendous stress levels

Thomas Lojek: What role has fear and the fear of failure in combat training?

Kris Paronto: Fear as a tool, as an element of training, including the fear of failure, has to be understood very well and where it has its place and where it doesn’t.

I think fear and the fear of failure is a necessary element when we are going through vetting or trying out for a Special Ops Unit or Top Tier Paramilitary Organization.

We need that sense of fear of failure to cause a little bit of stress.

It causes the cream to rise to the top and weeds out those that aren’t ready.

Normally the fear of getting kicked from the unit or being DNR’d is stress enough.

The fear of being kicked out of unit or losing my job if I didn’t pass a vetting or tryout gave me a sense of fear that was greater than any yelling or intimidation tactic ever did.

I was adequately prepared though, once I started in the PMC world, because that is the 75th Ranger Regiment.

There is the standard vetting that was called R.I.P which is now called R.A.S.P to make it into the 75th Ranger Regiment, then of course there’s Ranger School if you’ve been lucky enough to not be RFS from the unit before you have your turn to earn your Ranger Tab.

But even on a daily basis while serving with the 75th Rangers, we are continually being vetted.

There’s no lull, and if you screw up, then, at first, there are quite a few creative forms of physically demanding punishments.

And it is necessary.

It helps to remind us every day, who really wants to be there and sorts those that don’t out.

Because if guys can’t handle the daily grind, and I’m not even talking about R.I.P or Ranger School, which is its own special kind of hell, then they’re gonna quit on you shit really hits the fan.

But, I don‘t believe it’s valuable for open enrollment classes.

A participant coming to a Battleline class isn’t going to learn a damn thing if I’m screaming in their face, or making them elevate their feet and do push-ups until their arms come out of their sockets, or if I throw their optic across the range, because it wasn’t tightened down before we started.

(That last one really did happen at a well-known training site. It was uncalled for and completely unnecessary.)

Yes, it is valuable for “can you take this punishment?“ training environments where you are going downrange to be part of an elite team or Spec Ops Unit.

I did learn by fear, though, while becoming a Ranger with the 75th and also by joining GRS, but not by fearing an instructor who thought they were intimidating me with their thousand-yard stare.

The fear I learned from was my own self-generated fear, the fear of failing, the fear of not knowing what to expect and the fear of not living up to the standards I had set for myself.

Ranger School exemplified this kind of fear.

The Ranger instructors put us under tremendous stress levels, but it was great because it made me learn quickly.

We didn’t have the luxury to be told or shown how to complete a task multiple times.

The task, condition and standard was provided, and if we were lucky, it was demonstrated once and after that it was “It’s in your Ranger Handbook. Go find it Ranger!”

The fear of being put in charge at Ranger School coupled with the fear of failing, returning to 2/75 as a tabless bitch and the feeling of humiliation in front of all other guys that would come with it, made me understand that learning curves are quick but they can be obtained and it did help me become a better GRS operator later in my career.

Again though, this fear isn’t necessary for open enrollment classes.

No participant wants to pay to learn a skill, only to be humiliated in front of others.

We, as coaches/instructors, have to know when it’s time to add a little stress and when it’s time to mentor and be coaches.

I am blessed to understand both ways to learn and to teach.

Just another set of skills that were taught to me so I could put them in my kit bag to use when necessary.

We always look to build our participants up and not tear them down

Thomas Lojek: Do you use these principles in your courses?

Kris Paronto: Yes. We always at Battleline look to build our participants up and not tear them down.

We know there are different ways to accomplish the same tasks and not everyone is alike.

We do teach and maintain fundamentals as a base to learn from as fundamentals are the heart and soul of any coaching curriculum, but we also know that variables can affect a fundamental in which case we have to be fluid with our coaching style.

There are some instructors who belittle participants, sometimes to the point of humiliation and that crosses a line.

A good coach will never talk down to a participant.

They will always find a way to teach, mentor and demonstrate the proper course of action with patience.

Participants book a class to learn something or to work on their skill-set but not to be humiliated.

We all learn differently, but in the end we all want to learn the skills we need to feel secure in our daily lives.

As coaches, we need to find the best way to teach and mentor so a participant obtains that.

We don‘t yell or talk down to Battleline participants.

We mentor them, answer their questions, and motivate them to learn.

They do want a little bit of pressure to feel challenged but to not feel humiliated.

At Battleline, we are coaches.

Our belief of “We can always do better“ is something I was taught by coaches that I learned from in football when I was a kid.

We can be honest with each other when we screw up, but we always use the screw up as a learning point to improve on.

This goes full circle of what we discussed before: dogmatic or flexible?

We need to know what coaching style to use because it will fit into what your participant learning process requires at that point in their experience level.

If you have a first-time shooter and you yell at him like it was a Ranger Battalion training evolution, we will lose him/her and possibly a whole community of new shooters.

We lose new shooters in the 2a community because of unnecessary bravado or intimidation.

What I’d recommend to any coach/ instructor out there is if you have a course that needs yelling and screaming because you believe it adds extreme stress – make sure it is advertised correctly before the students show up at your range.

Let them know beforehand.

Some will love it and sign-up immediately.

Others will stay away, and this is how it has to be.

We need to provide environments that all can learn from in the open training and advertise it correctly.

I have a few courses that are built around high-stress levels.

And it is not yelling and screaming.

It is just physically intense and exhausting.

The stress level comes with heavy breathing and muscle fatigue.

We don‘t need to yell at them.

The intensity of physical training does the job over time better than intimidation or the blue box of death (pro timer).

At the end of the two days, the participants felt pushed and a sense of accomplishment.

So, to answer your question:

Open courses, in my opinion, should use a non-intimidating environment for best results.

Highly specialized training for Special Operations of specific units like big city SWAT teams also need a learning environment that’s coupled with high levels of stress deemed by their Team Leaders and Training cadre.

Those that fall in between this need to take it upon themselves to seek out the type of courses and training that they respond best to.

Learn from everyone and eventually you’ll find that coach/instructor that you respond best to.