Thomas Lojek

Article

Mark Human:

Lose Your Weapon – Lose Your Life!

The Truth About Weapon Access And Retention

11. November 2025

Mark Human is currently based in Cape Town, South Africa.

Mark has been a paid trainer for various South African Military, National and Provincial law enforcement departments, private law enforcement, security companies and local nature conservation team members.

His focus is on CQB, Specialized segments of HRT and “anormal” scenarios – to complement existing sound practices and skills.

For MDW Multidimensional Warriors (South Africa), Mark is head of training for curriculum and course development.

Official Sponsors

Many lessons over the last 25 years

02:00 my WhatsApp message binged.

As I woke, I felt for my phone next to the bed and mumbled to my wife, “I hope they haven’t started rioting again.”

A message from an armed reaction officer who works for one of my clients we provide training for came up on the screen.

It was worse than the message I expected.

It read: “Hi Mark, I have just found a reaction officer from one of the other companies stabbed to death next to his vehicle on Main Road. His firearm is missing; we found one casing, so we think he got a shot off.”

Since returning to South Africa in 1998, we have become accustomed to news of law enforcement and security officers being disarmed and killed for their firearms.

Dealing with these scenarios quickly became a priority focus, and I dare say an obsession.

Over the years we have adjusted and refined how we teach and deal with these scenarios.

We have learned many lessons over the last 25 years — below we highlight a few that have been key to maintaining the edge against the bad guys.

Good combative concepts and most self-defence or personal protection programs emphasize threat precursors.

Fast is good; early is better — the later you see things, the faster you have to be.

Recognition skills: 4 categories

We break these down into four categories — just an overview; this is by no means a breakdown of curriculum contents.

1. Situational recognition skills

These emphasise specific scenarios or areas, such as responding to a panic alarm, approaching possible suspects, or identifying choke points while driving an escort.

2. Autonomic recognition skills

These mean recognising pre-fight indicators such as posturing, grooming, and verbal tells.

3. Mechanical recognition skills

These are deliberate actions that indicate weapon access or concealment just prior to an actual attack.

Telling people to “watch the hands” is simply not enough.

These skills need to be specific — for example, an elbow cock that indicates access along the waistline.

4. In-fight recognition skills

These are physical reference points during the actual confrontation.

An example is a blade-wielding opponent using their check hand (non-weapon hand) as a measure for distance, a distraction, or for grabbing.

Recognising changes in range is key to linking and adapting skills and tactics to successfully counter attacks.

Frameworks for distance management

Frameworks for distance management are great tools, but it needs to be emphasised that in practice they are fluid and not written in stone.

Even if the initial engagement starts outside physical contact range, a committed opponent can close range surprisingly quickly.

With early recognition we are able to link actions to deny contact and create opportunity to access our handguns.

Frameworks can be expanded and compressed like a concertina depending on variables such as pressure, time of recognition, environment, method of attack, and mandate.

For this article we will keep it simple and break down access versus edged‑weapon and life‑threatening empty‑hand attacks:

7 meters and more — with early recognition: stand and deliver, or lateral move, draw from the holster and fire.

3.5 to 7 meters — with early recognition: lateral movement; move, draw and shoot while moving. In some cases this may mean moving offline in a backward‑arching trajectory.

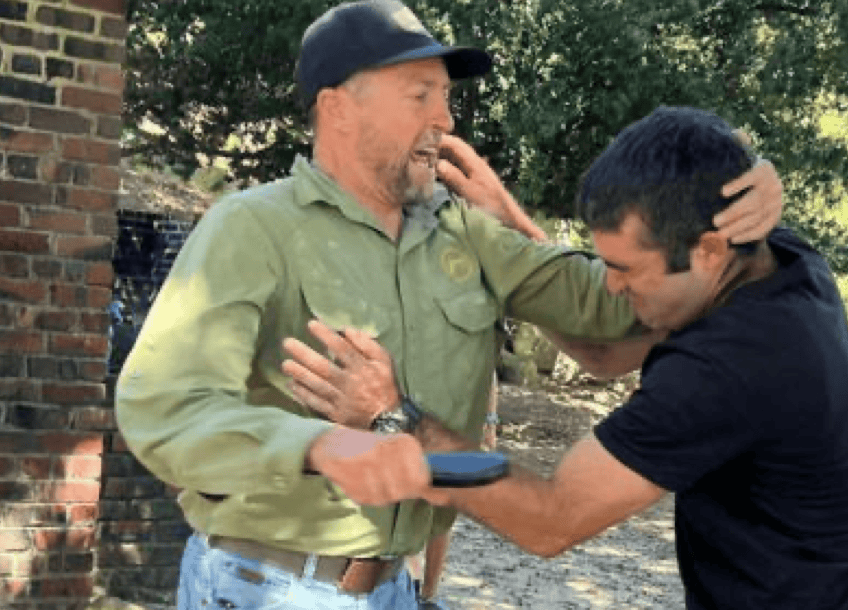

0–3 to 5 meters — this range requires empty‑hand skills to deal with the attack and to draw or create the time and positioning to access your weapon. It’s easy to get fixated on weapon access and get struck, grabbed, or stabbed if you ignore the incoming attack.

We use a simple acronym to help embed reflexes and avoid initial fixation on weapon access in these scenarios:

Deal — deal with the immediate attack.

Disrupt — disrupt the attacker’s intent and balance.

Deploy — deploy your weapon once you have created the space and time to do so safely.

In a world of chaos, oversimplification gets you dead.

Absolutes apply in specific contexts but crumble when things change up.

As a solo or small‑team operator/officer, you have to be able to adapt to a broad range of scenarios.

The “keep it simple, stupid” idea is a game of percentages and often tries to force one concept or skill as a solution to chaotic challenges with many variables.

Especially with edged weapons, a basic change in pressure can destroy what would be considered the panacea of edged‑weapon defence.

In other words: in a world of chaos, oversimplification gets you dead.

The breaking mechanism of branched decision‑making (the “what if / then / either‑or”) needs to be addressed constructively as part of structured training. Let’s look at two examples.

Imagine an attacker rushing forward at full speed with his blade hand held on his hip (narrow attack), waiting to stab you the moment he makes contact and grabs you with his front hand (delayed timing).

Now imagine an attacker at arm’s reach not committing into your immediate space but matching your footwork when you move forward or backward (neutral pressure), while using his blade to deliver quickly retracted reverse‑grip stabs (negative pressure — picking and snap cuts) to your face and neck area (broken‑timing attacks).

It’s obvious that two different skill sets are required to achieve a positive outcome; both scenarios require different solutions.

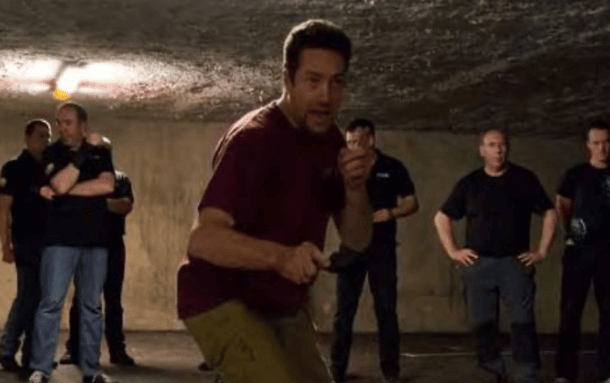

Our job as trainers is to understand and articulate changes in pressure and link a range of embedded options so operators can adapt and triumph under stress.

From a training‑provider perspective, this means more than watching YouTube (a useful resource) — it means spending a percentage of your time in the field with clients to understand their mandate, daily grind, and the threats they face.

Combat Sports: Good and bad

Combat sports provide excellent conditioning and attributes but need to be adapted to be congruent with the mentality, intent, and skills required to be effective against challenges faced in the field.

It is not uncommon to face a criminal with poor fighting skills in the traditional sense of the word but armed with street smarts and killing experience.

“They are not bound by your social values and no one told them not to bring a knife or screwdriver to a gunfight.”

Adapt your gun handling and targeting mindset for contact-range engagements

Simply carrying a firearm does not guarantee success — it is critical to combat mindset complacency and a false sense of security just because you have a sidearm strapped to your belt.

Contact-range shooting means you will draw and possibly fire one-handed, often with your non-gun hand forward of your muzzle to defend against edged-weapon attacks or grabs (please do not tell me there is no reason not to have both hands on your handgun while you are getting stabbed in the face).

These situations often require adapted draw strokes and shooting from “modern non-traditional” firing positions.

Centre-of-mass shots are not always available and adapted targeting should be practiced during training.

If contact-range access and retention are recognised priorities for officers, skills to deal with these challenges need to be structured to teach mindset, in-fight recognition, physical skills, expanded targeting, and adapted firearm safety.

Form follows function — adapt accordingly.

Stay safe out there!