Thomas Lojek

Interview with Kerry Alzner:

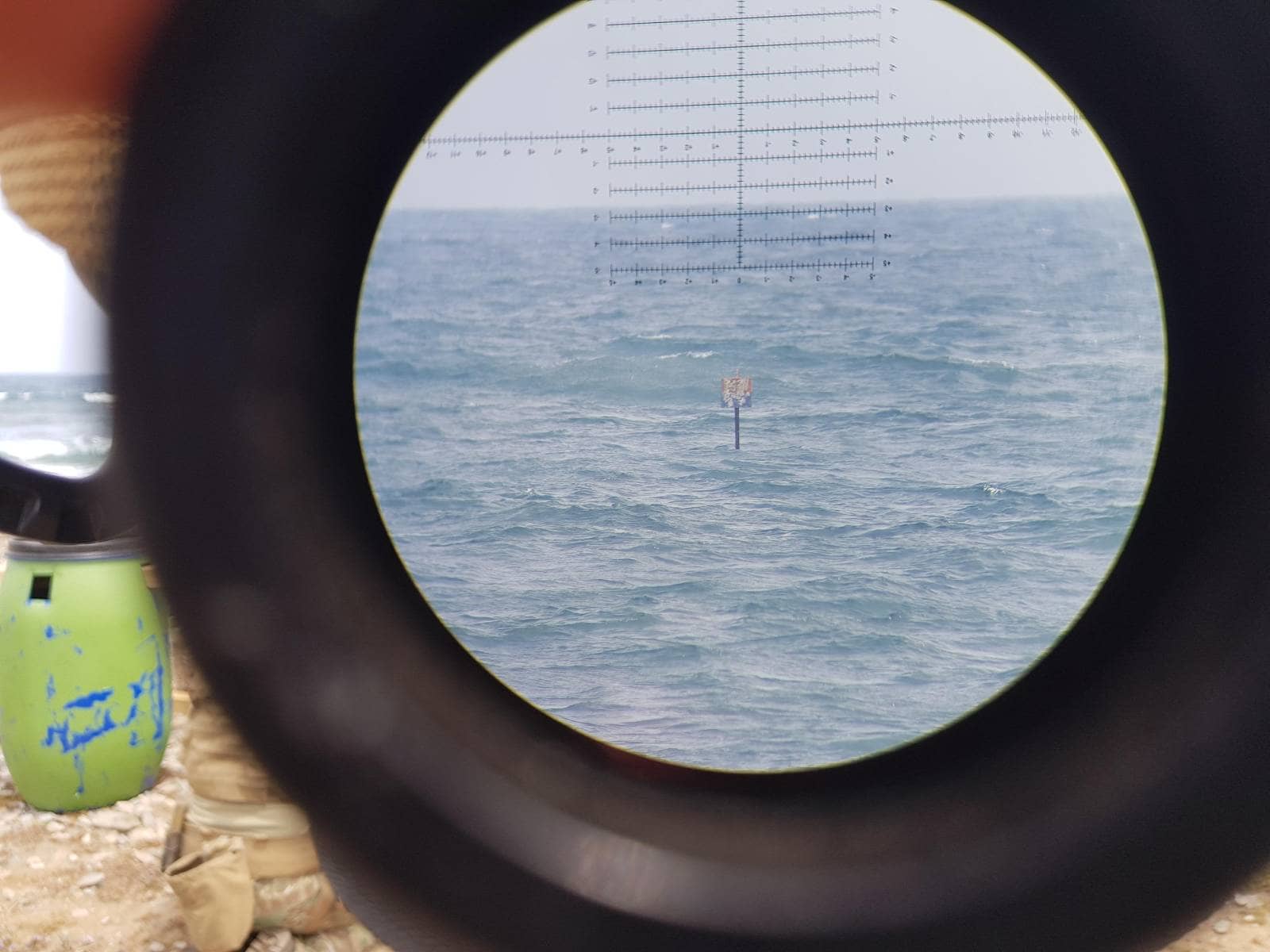

Vulnerability Assessments

and

Critical Infrastructure

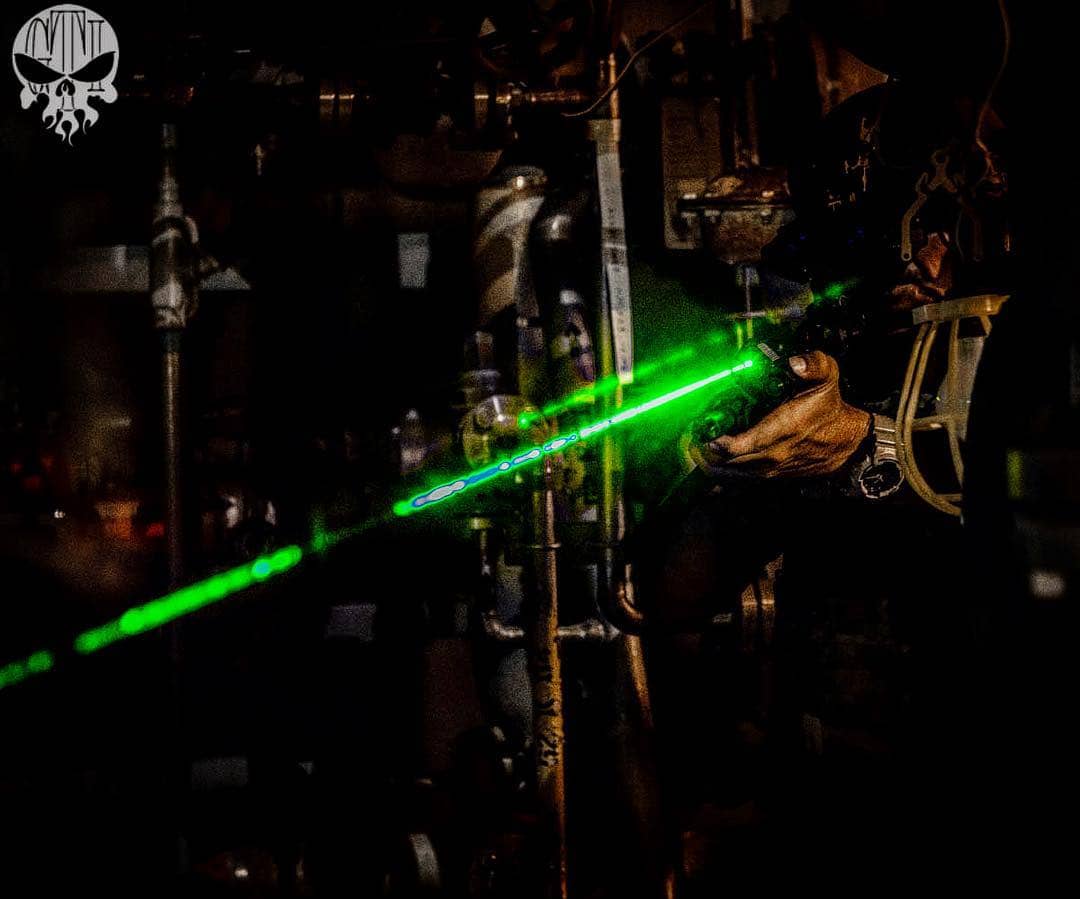

Kerry Alzner served more than 25 years with the U.S. Army, including over 15 years in Special Forces as a weapons and intelligence NCO.

He has conducted military-type training around the world in CQB, sniper operations, counterterrorist operations, heavy weapons, advanced driving, personal security (bodyguard) duties, vulnerability assessments, surveillance and countersurveillance, and survival.

He is a member of the cadre of instructors at GTI Government Training Institute in Barnwell, South Carolina.

Why Compliance Is Not Security: The Human Factor as the Primary Vulnerability

Thomas Lojek: Vulnerability assessments are often seen as necessary only after a security failure.

Imagine a data company that also handles government data.

It relies on local infrastructure, uses modern surveillance and state-of-the-art security measures, and is fully compliant with all relevant regulations.

From its perspective, everything is “done right.”

Why should such an organization still conduct a vulnerability assessment?

Kerry Alzner: I have to find a way to get into that system.

Some companies hire very good computer professionals and invest in AI, security layers, and firewalls to stop hackers from getting in or being misdirected.

But what many organizations don’t fully take into account is the human element.

A lot of people have personal vulnerabilities.

Some are lonely; some have relationship problems.

If you find someone like that inside the organization—man or woman—it becomes a human issue.

You start talking to them.

You build a relationship.

Maybe you date them; maybe you woo them a little.

Over time, trust develops.

They might ask for a picture to store on their smartphone, laptop, or computer.

Hidden inside that picture is a virus.

That’s just one way of getting access.

The old, hard-line approach—someone sneaking in, picking a lock, a James Bond–style operation—that’s old school.

Today, the modern approach is to get someone on the inside to do it for you, one way or another.

This has been done for years.

The Soviets did it.

Every national government has done the same thing to obtain intelligence from other agencies.

In the end, people are the weak link.

Technology Doesn’t Fail — People Do: The Illusion of Security in Automated Systems

Thomas Lojek: Does technology genuinely improve security, or has security become a more sophisticated zero-sum game—where advances in technology also create a false sense of confidence?

Kerry Alzner: Even with AI and modern computerized security systems, there is always risk.

These systems work—but we rely on them too much.

And very often, we don’t fully understand the human nature behind them: both the people operating these powerful systems and the very human tendency to ignore them.

Your alarm goes off.

Someone may be breaking into your house—but you’re at dinner, you’re having a good time, so you ignore it.

The technology works.

It warns you that there is a problem.

But did you actually respond to it?

Did you fix it?

Or did you just acknowledge it and move on?

In daily life, alarms go off all the time.

Take a simple home security system.

You come home and forget to turn it off, so it triggers.

The kids are in and out, and it triggers again.

You get tired of resetting it.

Eventually, you just turn it off “for now”—and then you forget.

So yes, we depend on technology.

But over time, we also start ignoring the very systems we depend on because they have alerted us so many times without a real incident.

Technology is valuable—but we always have to account for the human element behind the technology when it comes to security.

If You Want to Cripple a Society, Turn Off the Power: How Adversaries Think About Systemic Disruption

Thomas Lojek: Let’s step into the mindset of our adversaries for a moment.

If hostile actors were carefully assessing us right now—particularly in the Western Hemisphere—where do you think they would focus first in order to cause harm?

Kerry Alzner: Electricity.

How many people in Europe—and here in the United States—can’t function without their cell phones?

Realistically, an EMP-type weapon could take out significant parts of our systems.

And drones being used to target power plants and cut cities off from the grid, as we see in the war in Ukraine.

It would disrupt our ability to move.

Military and police personnel wouldn’t be able to get to their posts.

Streetlights, hospitals, transportation systems—I’ve stopped you from moving.

I can stop food from reaching people.

I can stop fuel and gas distribution.

I can cut off electricity so homes can’t be heated in winter.

By attacking the electrical grid, I can make an entire society vulnerable very quickly.

Critical Infrastructure Under Fire: Why Power Grids Remain Soft Targets

Thomas Lojek: In early January 2026, Berlin experienced a major power outage caused by deliberate sabotage of the electrical grid.

The attack cut electricity to roughly 45,000 households and more than 2,200 businesses, affecting up to 100,000 people in southwest Berlin, with losses of power, heating, and essential services in sub-zero winter conditions.

How would you advise policymakers to address this risk more efficiently in the future?

Kerry Alzner: When it comes to the electrical power grid, in my county, 55,000 people went without power for ten days in winter.

What happened was simple: these individuals drove up in a van to small substations and shot them up with AKs.

So how do you stop it next time?

You have to add cameras.

You can’t afford to place a human being on guard duty there all the time—and, again, humans fail.

So you need alarm systems.

You can harden the site so vehicles can’t just drive up and attack it.

But the real question is: how much money are you willing to spend to protect that one location?

This should have been a wake-up call across the country about protecting critical infrastructure.

But politicians don’t learn.

Too many people are focused on counting the money.

They don’t want to spend it to protect crucial infrastructure, and they don’t realize how much more it’s going to cost to fix the damage later.

If you want to learn more about Kerry Alzner’s training, or if you are interested in reaching out for a vulnerability assessment, please contact Kerry via GTI in South Carolina.

GTI’s multiple courses contain a cooperative curriculum base and ongoing research from a staff with extensive operational military and law enforcement experience.

Photos: Government Training Institute | Dave Young