Thomas Lojek

Tom Buchino:

The Importance of Small Unit Tactics (SUT)

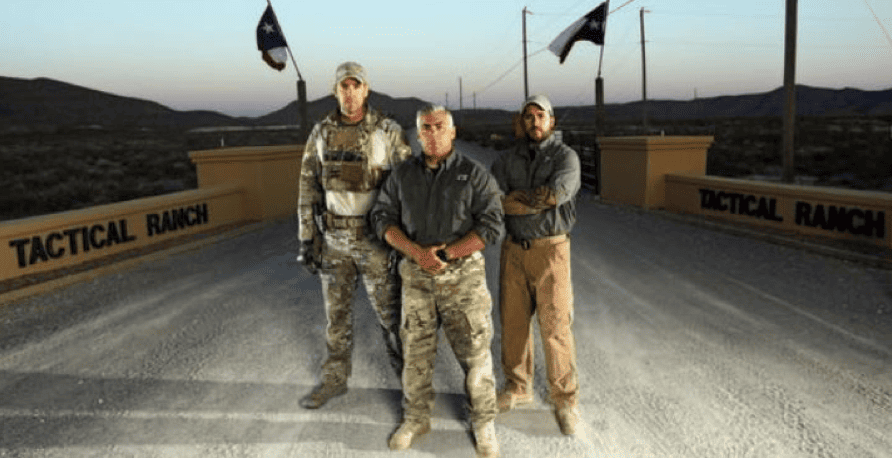

Tom Buchino, Sergeant Major, U.S. Army Special Forces (Ret.).

A decorated combat veteran with worldwide experience having served in multiple Special Forces Operational Groups, the Special Warfare Center and School, and a Counter-Drug Organization.

Founder and CEO of Covenant Special Projects and Tactical Ranch®, Texas.

The importance of Small Unit Tactics (SUT)

There is no such thing as advanced tactics; only perfect execution of the fundamentals under stress.

Everything we do as tactical operators, protective agents, law enforcement officers, and trainers must be rooted in the fundamentals.

Shoot – Move – Communicate!

Nothing else matters.

So, with that in mind, I choose to go a slightly different direction (yet mutually supporting to all my counterparts’ writings) in my contribution to this publication.

I’d like to address the importance of Small Unit Tactics (SUT).

I know from first-hand experience in the Special Forces Regiment that most battles are fought and won or lost by the composition of small teams.

A SEAL Platoon, SF A-Team, light infantry squad, or a few police officers responding to a school shooting fight with limited personnel, limited weapons systems, and limited supporting resources.

Success or failure hinges on factors including individual and collective skills (training and experience) and the immediate ability to operate as a Team, thus Small Unit Tactics.

As the owner of Covenant Special Projects Protective Services and our training facility, TACTICAL RANCH®, my instructor cadre and I ensure we stress the importance of proper execution of Small Unit Tactics.

Small Unit Tactics (SUT) encompasses all aspects of individual and collective element tactical competencies as well as the team’s doctrine, policies, procedures (SOP’s), and TTP’s.

SUT requires mental and physical discipline—the discipline to execute the trained behavior that best supports fellow teammate efforts and the ground-truth situation.

Small teams rely completely on one another; it’s critical to mission success.

Every operator must do his/her job and not “be the lone wolf,” possibly placing fellow teammates or the mission at risk.

SUT is like a tactical symphony; every instrument or operator has a supporting role.

One rogue violin out of key… One teammate performing something different from rehearsed SOP… Well, you get the picture.

The issue with developing robust SUT capabilities in small teams is that this aspect of training is often overlooked.

It’s much cooler and better for the Spotlight Ranger YouTube posts to simply allocate all training time to individual skills: El Presidente, tactical reloads, etc.

Of course, those of us who carry guns for a living or for defense purposes love to spend time at the range punching holes in paper or banging steel.

But all too often we neglect working scenarios involving others (teamwork / SUT).

The implementation of Small Unit Tactics training into team training

… because only Rambo can do it alone …

So, let’s break down SUT.

Think of SUT as the combination of everything administrative, historical, and tactical combined in an action.

An action that is based on a solid foundation of principles and doctrine.

Foundations are the sturdy, never-wavering, always-present blocks that support every structure, every business, and every successful tactical operator and operation.

Foundations (based on doctrine) support fundamentally based execution of an operation.

Now, foundations are seldom in view, often hidden and constructed of messy, not-pleasing-to-the-eye materials.

Yet when the molecular structure of these elements combines with just the right mixture, the result is nothing less than a solid platform for everything else to stand upon.

The implementation of SUT training into group or team training events is critical for mission readiness.

As previously stated, every aspect of individual and collective skills is combined into Small Unit Tactics.

Whether conducting a dismounted patrol through an Afghan village, counter-ambush immediate actions while operating a convoy in Syria, or serving a high-risk warrant in Chicago, the immediate action of team members during emerging events must be behavioral and decisive.

You have to determine your doctrine first

The application of doctrine for the combat deployment of smaller units in a particular environment.

In order to truly develop and implement SUT competencies in your small team’s training, you have to first determine your doctrine.

Military and most law enforcement elements have published doctrine, but occasionally we work with small teams that have yet to determine what their true mission is, let alone know anything about doctrine.

This deficiency leaves the team with no clue how to train and often leads to confusion in team members’ responses in emerging scenarios, resulting in diminished SUT competency.

Think of a part-time police SWAT team in a landlocked small rural county in the U.S. that wants to spend time training with borrowed boats on a river 150 miles outside their jurisdiction.

Maybe it is fun, and a great tanning opportunity, but what a waste of valuable training time.

It’s not relevant to their assigned directives.

Or that same SWAT team that has not developed a Tactical SOP (TACSOP) concerning entry operations; this could be catastrophic should officers not know their individual and supporting officers’ duties and responsibilities during the assault.

I know all this discussion of doctrine, SOPs, policy, procedures — blah, blah, blah — is not what gets tactical practitioners’ blood pumping.

For many of you, the behavioral response of such things is already ingrained in your soul from years of service.

But we, as trainers or unit leaders, have a responsibility to set our folks up for success.

Combat marksmanship speed and accuracy development is quantifiable; immediate results are noted by hits on steel or the tone of a pro timer.

But evaluation of SUT requires non-biased assessment of the team’s performance in a given scenario.

Stick with what is doctrine!

Scenarios must be of tactical relevance.

Each exercise must be followed by a facilitated After Action Review (AAR).

The AAR allows teammates to discuss their actions and the supporting actions of fellow team members from the planning phase through actions on the objective.

We develop lessons learned from the exercise and subsequent AAR, then revise (if necessary), rehearse, and evaluate.

This is an ongoing process that must evolve with the tactical environment.

Don’t waste time, resources, or energy on tactics or techniques that will (a) never be authorized by your agency or unit, and (b) are not a mission-essential task.

Stick with what is doctrine.

Doctrine consists of fundamental principles, tactics, techniques, and procedures, as well as terms and symbols.

Most of all, doctrine provides the fundamental principles of what works in battle, based on past experience.

These principles have been learned through combat and conflict, and although not always prescriptive in nature, they are authoritative and always the starting point for addressing new problems.

Such principles are not simply a checklist for what to do in a situation or a constraining set of rules.

These principles are designed to promote operator initiative and adaptation to solve problems.

With that in mind, once the team has identified their mission, the Mission Essential Task List (METL — the skills required to fulfill mission directives, specified and implied tasks), and accepted or developed and implemented department, agency, or unit policies, procedures, and standard operating procedures, they now have the basis for doctrine.

The team now knows what skills to train, how to develop team operability, and the best course of action for revising and sustaining capabilities.

All of this combined becomes the recipe for SUT development.

The tactical advantage when “shit hits the fan.”

My time serving on and leading small teams (Special Forces and Protective Services Teams) has ingrained the importance of SUT.

Knowing the learned behavior and immediate response for myself and my teammates in a given situation provides teams the tactical advantage when “shit hits the fan.”

When on the “X,” what do we all do to win?

That’s SUT.

SUT is not restricted to policing and military units; it must be trained and employed in any aspect of battle involving two or more operators.

Offensive, defensive, reconnaissance, and stability operations require SUT.

Traveling, traveling overwatch, bounding overwatch — all require SUT.

Get it?

Everything we do in this wonderful world of the fight involves Small Unit Tactics.

A SEAL Team supporting a Marine Task Force may have differing Tactical SOPs (TACOPS), however their doctrine is consistent, allowing them to operate in support of each other.

An SF HALO (Military Freefall) Team will have mission-specific aspects to their TACSOP but will integrate perfectly and operate alongside that SEAL Team.

We may differ slightly in composition and capabilities but operate cohesively because of common doctrine and training based on the fundamentals.

Infiltration and Movement to Contact

Never was this more clear than during a mounted patrol during the initial invasion into Iraq in 2003 (Unclassified).

Prior to the official kickoff of the coalition forces’ air campaign, a small group of Special Operations Forces (SOF) conducted an infiltration of Iraq to set up and secure an isolated abandoned airfield.

The mission was to conduct a clandestine infill of other SOF teams for reconnaissance operations from the secured airfield.

The airfield seizure team consisted of one SF A-Team, one SF B-Team (a small headquarters command-and-control element), and a handful of Air Force Combat Controllers.

Upon successful occupation and setup of the airfield, the SOF contingent received multiple small teams via prompt delivery from time-staggered blacked-out MC-130s.

With the successful and undetected infiltration of U.S. SOF operators complete, all were dispatched to different recon sectors.

The airfield team was then ordered to initiate movement north to Baghdad to get eyes on the Baghdad International Airport (then called Saddam International Airport / SIAP).

The small SOF element traveling in GMVs (ground mobility vehicles) and Toyota Tacomas was joined by a Civil Affairs (CA) section with two Humvees.

The CA section was integrated into the SOF convoy, placing their vehicles between the A-Team in the lead and the B-Team bringing up the rear.

The combined team pushed north in the dark and cold, reaching the Euphrates River crossing as the sun began to rise.

A final security halt prior to crossing the bridge provided the team confirmation that aerial intelligence indicated no insurgent presence.

Ambush on the Euphrates Bridge

As the team made their push over the bridge crossing the Euphrates, and all vehicles approached the southern downward slope of the bridge, the convoy became engulfed in enemy small-arms fire from all directions.

Front, rear, left, and right contact struck simultaneously as Fedayeen fighters—hidden in buildings and behind elevated rock walls—triggered the ambush the moment the patrol entered the kill zone.

Supporting the Fedayeen were multiple RPG teams and Soviet DShK heavy machine guns positioned at several roadway intersections.

The U.S. team’s options to break contact or fight through were decided for them when the Assistant Patrol Leader (at the rear of the convoy) identified that one vehicle had broken contact and was no longer in convoy order.

As SOF operators engaged targets with rifles, mounted machine guns, and Mk-19 grenade launchers from vehicles now accelerating at high speed, the call of the missing vehicle went out over the radio.

With the team fighting from their convoy and distance between vehicles growing, the trailing Tacomas held at an overwatch intersection and dismounted operators to recover the lost Civil Affairs vehicle.

This unfolded in the midst of a seemingly endless ambush of enemy fighters.

Supporting fires provided cover for the dismounted troops to maneuver and vector the wayward vehicle back into the convoy formation.

Both SF and Civil Affairs soldiers returned fire against repositioning enemy elements.

The commander and lead element located an open field, assembled there, established security, and set defensive positions while awaiting the trailing vehicles.

Upon arrival of all vehicles, the team prepared for counterattack.

Close Air Support and the Second Fight Through

To this point, the unit had sustained no serious casualties.

However, many of the vehicles had suffered numerous non-disabling hits.

Communications with higher headquarters were established and the situation reported.

A motivated U.S. Air Force TAC-P (attached to the team) dispatched Close Air Support from an A-10 Thunderbolt.

Due to enemy armor positioned north of the patrol, the determination was made to fight back through the ambush site and cross the Euphrates again.

The plan was briefed to all teammates and executed with the firepower support of the A-10.

The extended period required to coordinate air support, report the situation, and prepare for round two allowed the Fedayeen time to re-form and reposition for their counterattack.

Never go through an ambush a second time — that’s just common sense.

But when the options are tanks versus trucks, or insurgents in strong positions versus SOF operators and American troops carrying a mountain of ammunition, the answer is a no-brainer.

After positioning the Tacomas between the heavier Humvees and confirming the inbound A-10 run, the detachment began its violent egress through the city back toward the river crossing.

Round two proved more intense than the first.

But the A-10 showed no mercy.

The U.S. ground element’s speed and accurate fire exceeded what the enemy anticipated.

As the egressing U.S. forces suppressed enemy positions, the A-10 expended every round of its combat load on hardened targets and one unfortunate fighter fleeing on a motorcycle.

The team crossed the danger zone and moved south over the Euphrates to a secure rally point — all without a serious casualty.

Many of the vehicles looked like Swiss cheese, and one even died just after reaching safety.

But the team was secure and in a defensive posture.

Live to fight another day.

“One Team. One Fight.”

This brief overview of a contact in Iraq is not intended to showcase heroes (a word much overused these days), or to highlight a lack of perfect intelligence.

It is intended to emphasize the importance of Small Unit Tactics.

The U.S. forces involved in this five-hour battle on a hectic day in a foreign land remained poised in overwhelming odds and destroyed a large number of enemy forces by working together.

They succeeded by thinking intuitively, exercising initiative, and taking the fight to the enemy.

Special Forces, Civil Affairs, and U.S. Air Force troops — although serving in different units, with differing SOPs, training, and equipment — exercised the principles of Small Unit Tactics to fight.

“One Team. One Fight.”

Small Unit Tactics is a vital aspect of tactical training.

It is the combination of everything administrative, historical, and tactical combined in an action.

An action that is based on a solid foundation of principles and doctrine.

As we face new global threats and domestic disturbances will require increased vigilance on behalf of the Tactical Practitioner.

The future brings many unknowns, but I know that my team and I at Tactical Ranch® will continue to stress relevant, mission-specific, realistic tactical training.

We will continue to emphasize the importance of developing and enhancing SUT capabilities in every group we have the privilege to work with.

“One Team – One Fight.”

Tom Buchino

Sergeant Major

U.S. Army Special Forces (Ret.)

Owner, CSP Protective Services

Tactical Ranch®

“De Oppresso Liber”